Originally posted January 26, 2012

Republished from the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Disclaimer: The answers to the questions posed do not constitute legal advice. The OHRC continues to monitor the evolving situation and will update or add to these questions and answers on an ongoing basis as needed.

Policy on

Competing Human Rights

Ontario Human Rights Commission

-

ISBN: 978-1-4435-9248-2 Print

-

ISBN: 978-1-4435-9249-9 HTML

-

ISBN: 978-1-4435-9250-5 PDF

-

Approved by the Commission: January 26, 2012

-

Available in various formats

-

Also available on Internet: ohrc.on.ca

This document is undergoing formatting changes to ensure easy readability, but the content is essentially complete. We will be embedding or linking to citations.

Contents

Summary..............................................................3 Goals of policy......................................................3 Practical steps to reduce potential for conflict.....................4 What are competing rights?...........................................4 Examples of competing rights situations..............................5 Key legal principles.................................................5 Analysis for addressing competing human rights situations............6 Organizational process for addressing competing rights...............7 Conclusion...........................................................7 1. Introduction......................................................8 2. Practical steps to reduce potential for conflict.................10 3. Goals of this policy.............................................11 4. What are competing rights?.......................................12 4.1 Defining terms..................................................12 Human rights........................................................13 Legal entitlements..................................................13 Interests...........................................................13 Values..............................................................14 4.2 Examples of competing rights situations.........................14 4.2.1 Code right v. Code right......................................14 4.2.2 Code right v. Code legal defence..............................15 4.2.3 Code right v. other legislated right..........................16 4.2.4 Code right v. Charter right...................................16 4.2.5 Code right v. common law right................................16 4.2.6 International treaty right v. Code/Charter defence............17 4.2.7 Charter right v. Charter right................................17 5. Key legal principles.............................................18 5.1 No rights are absolute..........................................18 5.2 No hierarchy of rights..........................................19 5.3 Rights may not extend as far as claimed.........................20 5.4 Consider full context, facts and constitutional values..........22 5.4.1 Context and facts.............................................22 5.4.2 Underlying constitutional and societal values.................22 5.5 Look at extent of interference..................................25 5.6 Core of right more protected than periphery.....................26 5.7 Respect importance of both sets of rights.......................27 5.8 Defences found in legislation may restrict rights...............28 6. Analysis for addressing competing human rights situations........31 6.1 Stage One: Recognizing competing rights claims..................33 6.1.1 Step 1: What are the claims about?............................33 6.1.2 Step 2: Do claims connect to legitimate rights?...............34 6.1.3 Step 3: Do claims amount to more than minimal................... interference with rights?...........................................36 6.2 Stage Two: Reconciling competing rights.........................37 6.2.1 Step 4: Is there a solution that allows enjoyment............... of each right?......................................................37 6.2.2 Step 5: If not, is there a next best solution?................38 6.3 Stage Three: Making decisions...................................39 7. Organizational process for addressing competing rights...........40 7.1 Quick resolution................................................40 7.2 Full process....................................................40 7.3 Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) models.....................41 8. Conclusion.......................................................45 Appendix A: Purpose of OHRC's policies..............................46 Appendix B: Policy development process..............................47 Appendix C: OHRC framework..........................................49 Appendix D: Case examples for resolving competing rights............50 Appendix E: Suggested contents of an internal policy................59 Index...............................................................64

Summary

As people better understand their rights and wish to exercise them, some of those rights may come into conflict with the rights of others. This is especially true in Ontario's increasingly diverse and complex society. Conflicts can begin when an individual or group tries to enjoy or exercise a right, interest or value in an organizational context (e.g. in schools, employment, housing, etc.). At times, these claims may be in conflict, or may appear to be in conflict with other claims. Depending on the circumstances, for example, the right to be free from discrimination based on creed or sexual orientation or gender may be at odds with each other or with other rights, laws and practices. Can a religious employer require an employee to sign a "morality pledge" not to engage in certain sexual activity? Can an accuser testify wearing a niqab (a face veil worn by some for religious reasons) at the criminal trial of her accused? How do you resolve a situation where a professor's guide dog causes a severe allergic reaction in a student?

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, provincial human rights legislation (including the Ontario Human Rights Code) and the courts recognize that no rights are absolute and no one right is more important than another right. Our laws guarantee rights such as freedom of expression as well as protection against discrimination and harassment based on gender, creed, sexual orientation and disability, among other grounds. They require we give all rights equal consideration. The law also recognizes that rights have limits in some situations where they substantially interfere with the rights of others.

The courts have said we must go through a process on a case-by-case basis to search for solutions to reconcile competing rights and accommodate individuals and groups, if possible. This search can be challenging, controversial, and sometimes dissatisfying to one side or the other. But it is a shared responsibility and made easier when we better understand the nature of one another's rights and obligations and demonstrate mutual respect for the dignity and worth of all involved. Finding the best solution for maximizing enjoyment of rights takes dialogue and even debate.

Ontario's Human Rights Code says the Ontario Human Rights Commission's mandate includes reducing tension and conflict in Ontario's communities and encouraging and co-ordinating plans, programs and activities to do this. The OHRC has developed this Policy on Competing Human Rights to help organizations and individuals address difficult situations involving competing rights.

Goals of policy

The Policy on Competing Human Rights is intended to be a useful tool for individuals and organizations as they deal with different types of conflict. It sets out a process to analyze and reconcile competing rights that emphasizes specific objectives and considerations.

For example, everyone involved should:

- show dignity and respect for one another

- encourage mutual recognition of interests, rights and obligations

- facilitate maximum recognition of rights, wherever possible

- help parties to understand the scope of their rights and obligations

- address stigma and power imbalances and help to give marginalized individuals and groups a voice

- encourage cooperation and shared responsibility for finding agreeable solutions that maximize enjoyment of rights.

The approach in the policy can help organizations and decision-makers resolve and even avoid rights conflicts altogether. Where litigation cannot be avoided, the policy provides a framework that can be used by courts and tribunals as they deal with these types of conflicts.

Practical steps to reduce potential for conflict

Employers, housing providers, educators and other responsible parties covered by the Ontario Human Rights Code have the ultimate responsibility for maintaining an inclusive environment that is free from discrimination and harassment, and where everyone's human rights are respected. As part of this, organizations and institutions operating in Ontario have a legal duty to take steps to prevent and respond to situations involving competing rights.

Organizations can reduce the potential for human rights conflict and competing rights situations by:

- being very familiar with the Ontario Human Rights Code and with their obligations under it

- taking steps to educate and train responsible individuals on competing rights situations and the OHRC's Policy on Competing Human Rights

- having in place a clear and comprehensive competing rights policy that:

- sets out the process to be followed when a competing rights situation arises

- alerts all parties to their rights, roles and responsibilities

- commits the organization to deal with competing rights matters promptly and efficiently.

Taking proactive and effective steps to address competing rights matters will help to protect organizations from liability if they are ever named as a respondent in a human rights claim involving competing rights.

What are competing rights?

In general, competing human rights involve situations where parties to a dispute claim that the enjoyment of an individual or group's human rights and freedoms, as protected by law, would interfere with another's rights and freedoms. This complicates the normal approach to resolving a human rights dispute where only one side claims a human rights violation. In some cases, only one party is making a human rights claim, but the claim conflicts with the legal entitlements of another party or parties.

While many situations may at first appear to involve competing rights, one must recognize that not all claims will be equal before the law: some claims have been afforded a higher legal status and greater protection than others. For example, international conventions, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, provincial human rights legislation and legal decisions all recognize the paramount importance and unique status of human rights.

Other non-human rights-related rights may also be protected in legislation, but may not have the same status that human rights do. Claims may also be based on interests or values held by individuals or groups.

While there are many situations in which rights, interests, and values may seem to conflict or compete, when evaluating situations of competing rights, human rights and other legally codified rights will usually hold a higher status than interests and values. The OHRC's Policy on Competing Human Rights is meant mainly to be a tool for resolving situations where there is a conflict of human rights and rights that are legally protected.

Examples of competing rights situations1

A competing human rights situation exists when legally protected rights are present in both claims, and at least one of the claims connects to human rights law. Based on this definition, allegations of competing human rights scenarios might include:

- Code right v. Code right

- Code right v. Code legal defence

- Code right v. other legislated right

- Code right v. Charter right

- Code right v. common law right

- International treaty right v. Code/Charter defence

- Charter right v. Charter right.

Key legal principles2

While the courts have not set a clear formula or analytical approach for dealing with competing rights, legal decisions have identified a number of fundamental principles that provide direction on how to deal with these types of scenarios, as well as what to avoid. The courts have recognized that the specific facts will often determine the outcome of the case and claims should be approached on a case-by-case basis. The main legal principles that organizations must consider when they deal with competing rights situations are:

- No rights are absolute

- There is no hierarchy of rights

- Rights may not extend as far as claimed

- The full context, facts and constitutional values at stake must be considered

- Must look at extent of interference (only actual burdens on rights trigger conflicts)

- The core of a right is more protected than its periphery

- Aim to respect the importance of both sets of rights

- Statutory defences may restrict rights of one group and give rights to another.

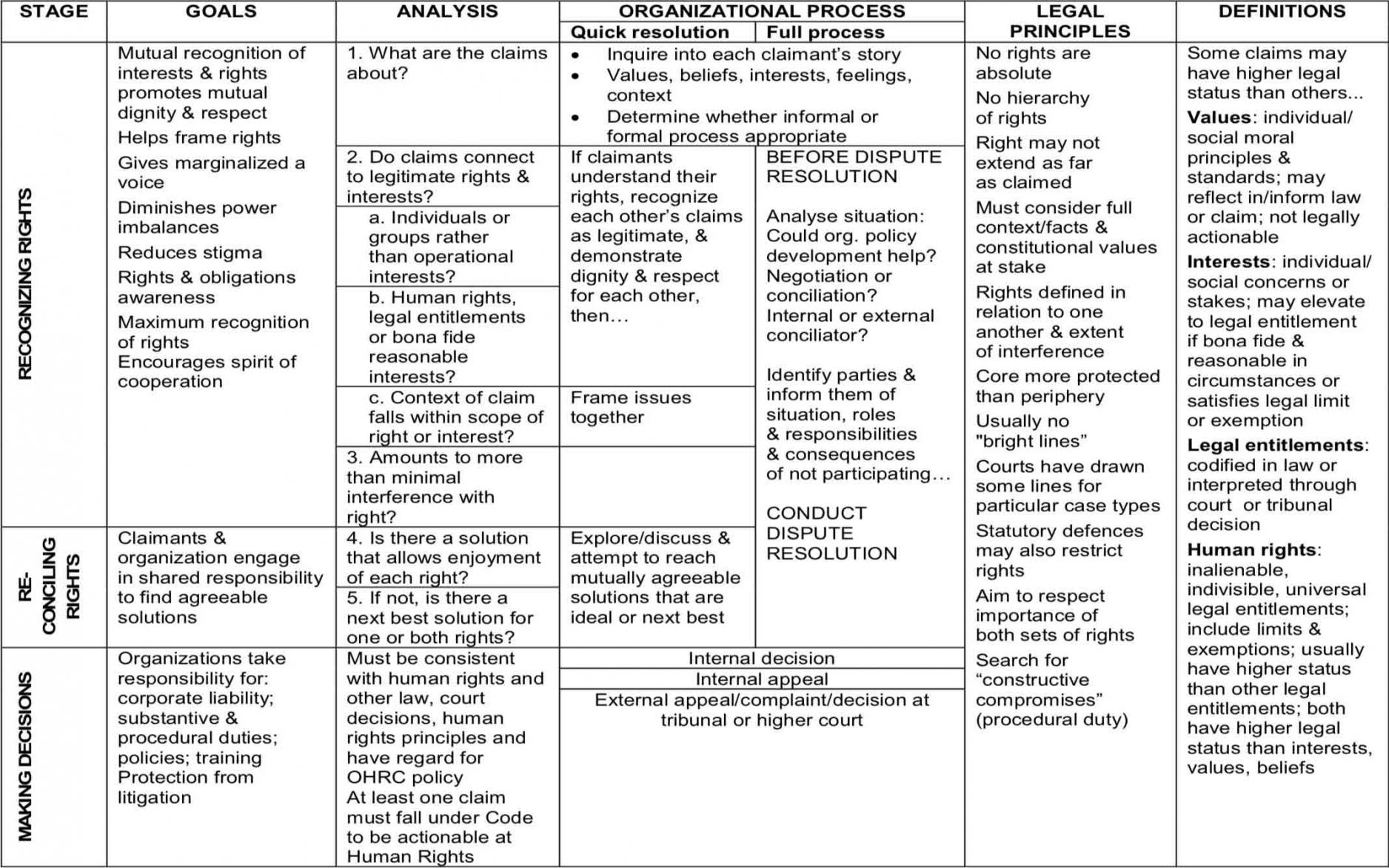

Analysis for addressing competing human rights situations

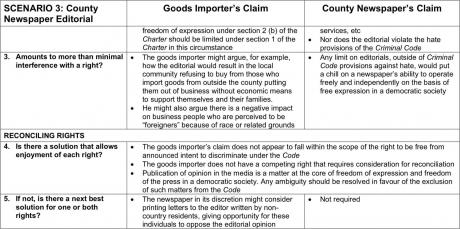

The Policy on Competing Human Rights includes a framework for addressing competing rights that the OHRC developed based on international human rights principles, case law, social science research, and consultation with community partners and stakeholders.3 The following table summarizes the framework's three-stage, five-step process for recognizing and reconciling competing human rights claims:

Process for addressing competing human rights situations

-

Stage One: Recognizing competing rights claims

- Step 1: What are the claims about?

- Step 2: Do claims connect to legitimate rights?

- (a)Do claims involve individuals or groups rather than operational interests?

- Do claims connect to human rights, other legal entitlements or bona fide reasonable interests?

- Do claims fall within the scope of the right when defined in context?

- Step 3: Do claims amount to more than minimal interference with rights?

-

Stage Two: Reconciling competing rights claims

- Step 4: Is there a solution that allows enjoyment of each right?

- Step 5: If not, is there a "next best" solution?

-

Stage Three: Making decisions

- Decisions must be consistent with human rights and other laws, court decisions, human rights principles and have regard for OHRC policy

- At least one claim must fall under the Ontario Human Rights Code to be actionable at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario

.

By implementing the OHRC's proposed approach, organizations can be confident that they have a conflict resolution process in place that is consistent with human rights principles.

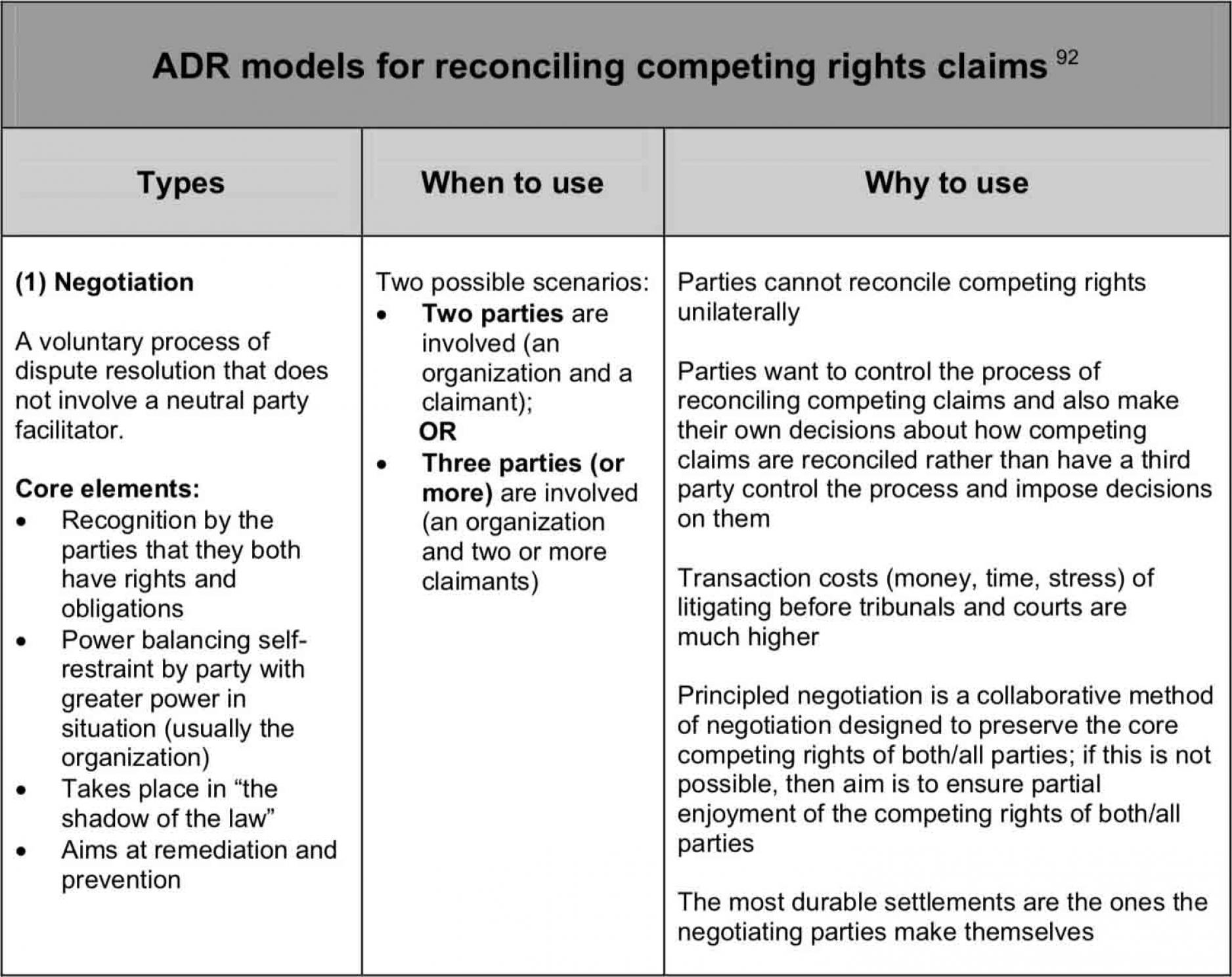

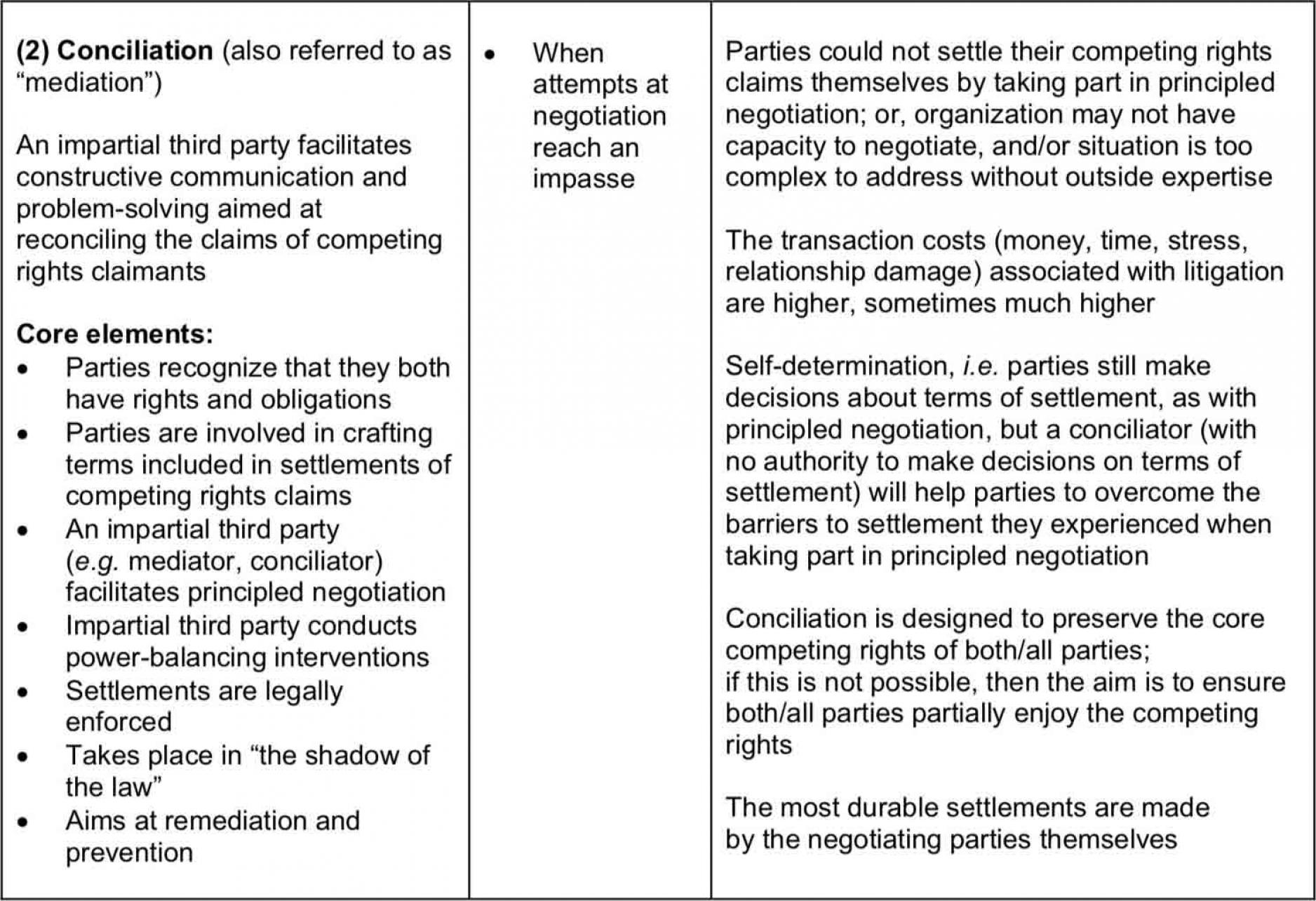

Organizational process for addressing competing rights4

Many competing rights situations can be quickly resolved through an informal process that may involve no more than one or two meetings. At the outset, organizations should consider whether the situation is suited to an informal and expedited process. For example, the facts of the situation and the framing of each claim may be straightforward and not in dispute. The parties may already be well-informed about each other's claims, rights and obligations. They may have shown respect for each other's interests and be willing to engage in discussions about solutions without delay.

A quick process will generally involve running through the analysis with both parties in a quick way. The focus here is less on a precise analysis of the rights at play, and more on finding solutions that benefit all sides and respect human rights. If the informal, quick process does not resolve the issue, then the organization may decide to use a full and more formal process. However, it is important to consider a quick resolution process first because workable solutions can be found relatively quickly in most cases of competing rights claims.

In a full, more formal process, the framework is applied more rigorously at Stage One to find out if a genuine competing human rights situation exists. If, after going through Stage One, an organization concludes that a competing human rights situation does exist, Stage Two will help guide it through the reconciliation process. The Policy on Competing Human Rights proposes an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) model to guide organizations through the Three Stage Analysis.

Conclusion

Competing human rights situations will inevitably arise in many different contexts, including workplaces, housing and schools. By following the approach outlined in the Policy on Competing Human Rights, organizations may be able to resolve tension and conflict between parties at an early stage. Resolving conflict early helps organizations to address matters before they fester and become entrenched. This in turn helps ensure the health and functioning of an organization, and can avoid costly and time-consuming litigation.

"All human beings are born free and equal

in dignity and rights." 5

1. Introduction

As they interact with each other, individuals and organizations will encounter situations of tension and conflict. This is especially true in Ontario's increasingly diverse and complex society. Conflicts can begin when an individual or group tries to enjoy or exercise a right, interest or value in an organizational context (e.g. in schools, employment, housing, etc.). At times, these claims may be in conflict, or may appear to be in conflict with other claims. Depending on the circumstances, for example, the rights to be free from discrimination based on creed or sexual orientation or gender may be at odds with each other or with other rights, laws and practices. How do you resolve a situation where a religious employer requires an employee to sign a "morality pledge" not to engage in certain sexual activity? Or, where a woman wants to testify wearing a niqab (a face veil worn by some for religious reasons) at the criminal trial of her accused? Or, where a professor's guide dog causes a student to have a severe allergic reaction?

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter), provincial human rights legislation and the courts recognize that no rights are absolute and no one right is more important than another right. Our laws guarantee rights such as freedom of expression and protection against discrimination and harassment based on gender, creed, sexual orientation and disability, among other grounds. They require that all rights be given equal consideration. The law also recognizes that rights have limits in some situations, particularly where they substantially interfere with the rights of others.

In recent years, competing human rights claims have emerged as a challenging issue for human rights commissions across Canada. The Ontario Human Rights Commission (the OHRC) has found that human rights claims increasingly involve situations where it appears that multiple claims are at stake. For example, a claimant may say that their statutory human rights have been violated by a respondent who then, in turn, claims a defence that is also established by human rights legislation. The human rights grounds most often cited in competing human rights claims include gender, creed, sexual orientation and disability, although other grounds and legal rights have also been invoked.

Ontario's Human Rights Code (the Code) says the OHRC's mandate includes reducing tension and conflict in Ontario's communities and encouraging and co-ordinating plans, programs and activities to do this. The OHRC has developed this policy to help address difficult situations involving competing rights.

Case law dealing with competing human rights claims has been developing slowly in Canada. The courts have said we must go through a process on a case-by-case basis to search for solutions to reconcile competing rights and accommodate individuals and groups, to the greatest extent possible. This search can be challenging, controversial, and sometimes dissatisfying to one side or the other. But it is a shared responsibility and will be made easier when we better understand the nature of one another's rights and obligations and show mutual respect for the dignity and worth of everyone involved. Finding the best solution for maximizing enjoyment of rights takes dialogue and even debate. To this end, there is a clear need for human rights policy guidance to supplement legal interpretation.

The OHRC has found that public debates on competing rights often relate to the presence of minority communities and how far the dominant culture should accommodate the rights of these groups. For example, in the post 9/11 world, various cultural and religious practices of Muslims have been called "inappropriate" or "unacceptable" by elements of the majority culture. These scenarios have commonly been referred to as matters of "competing rights" in the media. Others have questioned the extent to which publicly-funded schools ought to incorporate recognition of and respect for sexual diversity, including diverse family forms such as same-sex families.

The Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, has extensive experience in the areas of human and Charter rights. She has written:

- We need human rights. Whether we like it or not, religious, ethnic and cultural diversity is part of our modern world - and increasingly, part of our national and community reality. Human rights and the respect for every individual upon which they rest, offer the best hope for reconciling the conflicts this diversity is bound to generate. If we are to live together in peace and harmony - within our nations and as nations in the wider world - we must find ways to accommodate each other.6

The OHRC engaged in extensive background work to develop this policy. In addition to conducting legal and social science research, the OHRC developed a detailed case law review on competing rights.7 The OHRC also met with a wide range of individuals and organizations that either deal directly with competing rights situations, or have significant expertise in the area. For more detail on the policy development process, see Appendix B.

2. Practical steps to reduce potential for conflict

Employers, housing providers, educators and other responsible parties covered by the Code have the ultimate responsibility for maintaining an inclusive environment that is free from discrimination and harassment, and where everyone's human rights are respected. Organizations and institutions operating in Ontario have a legal duty to take steps to prevent and respond to situations involving competing rights.

There are proactive and practical steps that organizations should take to help reduce the potential for human rights conflict and competing rights. Organizations should be very familiar with the Code and with their obligations under it. They should take steps to educate and train responsible individuals on competing rights situations and the OHRC's Policy on Competing Human Rights.

It may be helpful for organizations to think of their responsibility to deal with competing rights matters as parallel to their already existing responsibilities relating to the human rights accommodation process. Organizations might consider assigning the responsibility for handling competing rights situations to the same people that are already responsible for dealing with accommodation issues. It could be the job of these people to educate and train others (including new staff), to monitor their environments to detect trends relating to competing rights, etc.

Employers, housing providers, educators and other responsible parties can help promote a healthy and inclusive environment for individuals protected by the Code by having a clear and comprehensive competing rights policy. The policy should include the process to be followed when a competing rights situation arises, alert all parties to their rights, roles and responsibilities, and commit the organization to deal with competing rights matters promptly and efficiently. An effective competing rights policy supports the equity and diversity goals of organizations and institutions and makes good business sense. For more detail on the suggested contents of an internal policy, see Appendix E of this policy.

Everyone in an organization should be aware of the policy and the steps for resolving complaints. This can be done by:

- giving policies to everyone as soon as they are introduced

- making all employees, tenants, students, etc. aware of them by including the policies in any orientation material

- training people, especially people in positions of responsibility, on the contents of the policies, and providing ongoing education on competing rights issues.

Tribunals and courts often find organizations liable, and assess damages, based on failure to respond appropriately to address discrimination and harassment. Some things to consider when deciding whether an organization has met its duty to respond to a human rights claim include:

- what procedures were in place to deal with discrimination and harassment

- how promptly the organization responded to the complaint

- how seriously the complaint was treated

- resources made available to deal with the complaint

- whether the organization provided a healthy environment for the person who complained

- how well the action taken was communicated to the person who complained.

Taking proactive and effective steps to address competing rights matters will help to protect an organization from liability if it is ever named as a respondent in a human rights claim involving competing rights.8

3. Goals of this policy

The main goal of this policy is to provide clear, user-friendly guidance to organizations, policy makers, litigants, adjudicators and others on how to assess, handle and resolve competing rights claims. The policy will help various sectors, organizations and individuals deal with everyday situations of competing rights, and avoid the time and expense of bringing a legal challenge before a court or human rights decision-maker.

It is in keeping with promoting social harmony to ensure that effective conflict resolution mechanisms are in place to address various types of conflict. This policy provides a framework for addressing competing rights situations that can be used as is, or adapted to meet the specific needs of individual organizations.

The courts have been clear that context is crucial in competing rights cases and each situation must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. This policy is intended to be a useful tool for individuals and organizations as they deal with different types of conflict. It sets out a process, based in existing case law, to analyze and reconcile competing rights. This process is flexible and can apply to any competing rights claim under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, provincial or federal human rights legislation or another legislative scheme.

The process builds in specific objectives and considerations for the organizations and indiv iduals involved. They should:

- show dignity and respect for one another

- encourage mutual recognition of interests, rights and obligations

- facilitate maximum recognition of rights, wherever possible

- help parties to understand the scope of their rights and obligations

- address stigma and power imbalances and help to give marginalized individuals and groups a voice

- encourage cooperation and shared responsibility for finding agreeable solutions that maximize enjoyment of rights.

The approach in this policy can help organizations and decision-makers resolve and even avoid apparent rights conflicts altogether. But in some cases litigation may be unavoidable, particularly where matters prove to be too complex to resolve informally, where parties are not willing to take part in the reconciliation process, or where all concerned may want the guidance of a court or tribunal.

4. What are competing rights?

In general, competing human rights involve situations where parties to a dispute claim that the enjoyment of an individual or group's human rights and freedoms, as protected by law, would interfere with another's rights and freedoms. This complicates the normal approach to resolving a human rights dispute where only one side claims a human rights violation. In some cases, only one party is making a human rights claim, but the claim conflicts with the legal entitlements of another party or parties.

4.1 Defining terms

Although there may be a perception that a competing rights situation exists, one must recognize that not all claims will be equal before the law: some claims have been afforded a higher legal status and greater protection than others. For example, after World War II, the United Nations enshrined the paramount importance of human rights in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Declaration opens:

- Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…9

Legal systems around the world have responded to this universal commitment to world peace by granting special protection to human rights. Canada recognizes the unique status of human rights in its Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a comprehensive list of rights and fundamental freedoms entrenched in the Constitution of Canada that is intended to unify Canadians around a set of principles that embody those rights.

In Ontario, the provincial legislature included a primacy clause in the Ontario Human Rights Code, giving it the ability to trump other provincial legislation. Courts have also commented on the "quasi-constitutional" status of human rights legislation and stated the importance of interpreting the guaranteed rights in a broad and purposive manner that best ensures that society's anti-discrimination goals are reached.

The following frequently used terms are defined in an attempt to show how they are distinguishable from one another.

Human rights

Human rights are inalienable, indivisible, universal entitlements codified in international and domestic law. In Canada, they are protected and interpreted through:

- the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- provincial-territorial human rights legislation

- decisions of tribunals and courts

- human rights commission policy statements, interventions and other mandated functions

- international law/instruments (ratified treaties, treaty body comments/ decisions, international and other jurisdictional court decisions).

Statutory human rights are also accompanied by defences, as set out in human rights legislation, and sections of the Charter. For example, the right to freedom of expression guaranteed by section 2(b) of the Charter may be circumscribed by reasonable limits as contemplated in section 1 of the Charter.10 A person's right to freedom of expression may be limited, for example, where their views incite hatred toward an identifiable group.

Legal entitlements

For the purposes of this policy, legal entitlements are non-human rights-related rights that are also codified in legislation (e.g. the Occupational Health and Safety Act and the Residential Tenancies Act), and the common law (i.e. case law). They are rights that are legally actionable: for example, the violation of a person's right to "reasonable enjoyment" of their rental housing could be litigated in Ontario before the Landlord and Tenant Board, the adjudicative body that administers the Residential Tenancies Act.

Interests

An interest is a matter in which someone has a personal concern, share, portion or stake. Interests may be societal and/or individual. Although interests are not legal rights, they are sometimes misunderstood and misclassified as such. In some cases, an interest could be elevated to the status of a right, if it is validated by a legal body. For example, a court or tribunal could find that an interest is bona fide (genuine) and reasonable in the circumstances: "the best interests of the child" have been given a high legal status and used by courts and tribunals to determine a wide range of issues involving children. Or, a court could find that an interest is of such magnitude that it constitutes a reasonable limit under section 1 of a Charter right. For example, the Supreme Court of Canada has held that a requirement that all licensed drivers be photographed, even though it interfered with the right to freedom of religion of Hutterites, was justified under section 1 of the Charter due to the state's interest in preventing identity theft and fraud.11

Values

Values are moral principles, standards, and/or things that a person (or group) believes are vital for achieving "the good" or excellence in any sphere of life. Some values may be reflected in law. For example, the Preamble to the Code is informed by the principles of mutual respect and the recognition of the dignity and worth of every person. Generally, however, values are subjective and not legally actionable in and of themselves. Understanding the individual or social values that may underlie a human rights claim will help parties and may inform its ultimate disposition. For example, in Ross v. New Brunswick School District No. 15, the Supreme Court of Canada gave special recognition to the importance of public education and the vulnerability of children when it unanimously upheld a human rights Board of Inquiry finding that a teacher's off-duty anti-Semitic comments undermined his ability to fulfill his functions as a teacher. The Court concluded that the Board of Inquiry was correct in concluding that his continued employment as a teacher constituted discrimination in public education.12

There are many situations in which rights, interests, and values seem to conflict or compete. When evaluating situations of competing rights, human rights and other legally codified rights will usually hold a higher status than interests and values. However, in some circumstances, interests and values may represent reasonable limits on rights and human rights, as envisioned by section 1 of the Charter. This policy is meant mainly to be a tool for resolving situations where there is a conflict of human rights and rights that are legally protected.

4.2 Examples of competing rights situations

A competing human rights situation exists when legally protected rights are present in both claims, and at least one of the claims connects to human rights law. Based on this definition, allegations of competing human rights scenarios might include the following:

4.2.1 Code right v. Code right

The Ontario Human Rights Code prohibits discrimination based on 15 grounds: race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, age, marital status, family status, disability, receipt of public assistance (in housing only), record of offences (in employment only). Competing rights claims may potentially arise relating to any Code ground. However, situations of conflict often involve creed, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, marital status or disability.

- Example: A civil marriage commissioner objects to performing a marriage ceremony for a same-sex couple, claiming that it violates his religious beliefs. He claims that under the Code, he has the right to be free from discrimination based on religion in employment. The couple wishing to receive the service claims that their right under the Code to be free from discrimination because of sexual orientation in services is being breached.13

It is also possible for competing claims to involve the same ground.

- Example: A college professor's guide dog is affecting one of her students who has a severe allergy to dogs. Both individuals might make Code-based human rights claims on the ground of disability.

4.2.2 Code right v. Code legal defence

In addition to providing protection from discrimination based on specific enumerated grounds, the Code includes exemptions that may act as a defence to a claim of discrimination. In many cases, these exemptions are deliberate attempts by those who wrote the legislation to address and help resolve situations where rights might compete.14

- Example: A religious organization, providing supportive group living to persons with disabilities of any denomination, requires staff to abide by a religious code of behaviour. The organization dismisses a support worker once it learns she is in a same-sex relationship. The dismissed worker might claim Code-based discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation while the religious organization might claim a Code defence under section 24(1)(a) that allows restrictions on terms of employment for religious and other types of organizations in certain circumstances.15

4.2.3 Code right v. other legislated right

In some cases, competing rights claims may involve Code grounds and other legal entitlements.

- Example: Some parents want the Ministry of Education to modify its sex education curriculum so it does not interfere with their beliefs: some for religious-based reasons, some for personal reasons. Other parents support the new curriculum changes: some based on the Code ground of family status and sexual orientation. Others want the new curriculum, based on the legislated right to public education. Parents opposed to certain types of sex education because of their beliefs might claim discrimination on the Code ground of creed. Other parents might claim a Code right based on family status, sexual orientation and a legislated right to a curriculum based on the broader purpose and requirements of the Education Act.

4.2.4 Code right v. Charter right

There may be situations where rights that are protected under the Code may compete with rights guaranteed by the Charter.

- Example: A man describing himself as a "born again" Christian often discusses his new religious enthusiasm with his employees. He has tried several times to encourage workers to come to his church meetings, and for Christmas gives each employee a Bible as a gift. Employees have made it clear that they do not welcome or appreciate his comments and conduct in their secular workplace.

The employees could argue that the Code right to be free from discrimination based on creed includes the right not to be subjected to proselytizing at work. The employer might argue that he is exercising his freedom of expression rights under the Charter.

4.2.5 Code right v. common law right

In some cases, a right protected by the Code may bump up against a right established by common law.

- Example: A Jewish family is asked to remove a temporary sukkah hut placed on their balcony for religious celebration because it does not comply with the condominium's by-laws and is said to be interfering with the neighbours' enjoyment of their balcony. The Jewish family claims discrimination on the ground of creed while the condominium co-owners might claim a right to peaceful enjoyment of property based on common law.16

4.2.6 International treaty right v. Code/Charter defence

Canada has signed and ratified many different international human rights conventions, some of which include complaint mechanisms. There may be situations where rights set out in these treaties conflict with domestic rights and obligations.

- Example: Non-Catholic religious school users claim a right to non-discriminatory religious school funding based on provisions of the United Nations' International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 17 The UN treaty body responsible for the Covenant found that Ontario's public funding of the Catholic school system to the exclusion of all other religions was discriminatory.18 The Ontario government relied on provisions of the Education Act, an exemption in the Human Rights Code, the Charter and related case law in its defence.

4.2.7 Charter right v. Charter right

There may be situations where one person's rights under the Charter may compete with another person's Charter rights.

- Example: A number of decisions dealing with the production of medical or other sensitive records in court or tribunal proceedings have considered the relationship between privacy and equality rights and the right to make full answer and defence, all rights protected by the Charter. In R. v. O'Connor, a case in which the accused was charged with a number of sexual offences, the Supreme Court of Canada established a procedure for determining when a victim's medical and therapeutic records, in the possession of third parties such as physicians, must be released to the accused for meaningful full answer and defence.19

5. Key legal principles20

While the courts have not set a clear formula or analytical approach for dealing with competing rights, they have provided some guidance. Where rights appear to be in conflict, Charter principles require decision-makers to try to "reconcile" both sets of rights. Although there are no "bright-line rules"21 for dealing with competing rights claims, legal decisions have identified a number of fundamental principles that provide direction in how to deal with these types of scenarios, as well as what to avoid.22 The courts have recognized that the specific facts will often determine the outcome of the case. Therefore many of the principles are abstract, and allow for some flexibility in approaching claims on a case-by-case basis. While many of these principles arose in the context of Charter litigation, they also provide guidance for other types of human rights conflicts:

- No rights are absolute

- There is no hierarchy of rights

- Rights may not extend as far as claimed

- The full context, facts and constitutional values at stake must be considered

- Must look at extent of interference (only actual burdens on rights trigger conflicts)

- The core of a right is more protected than its periphery

- Aim to respect the importance of both sets of rights

- Statutory defences may restrict rights of one group and give rights to another.

Organizations must consider these legal principles when they deal with competing rights situations.

5.1 No rights are absolute

-

A consistent principle in the case law is that no legal right is absolute, but is inherently limited by the rights and freedoms of others.23 In R. v. Mills, Supreme Court of Canada Justice McLachlin (as she then was) and Supreme Court of Canada Justice Iacobucci stated:

- At play in this appeal are three principles, which find their support in provisions of the Charter. These are full answer and defence, privacy, and equality. No single principle is absolute and capable of trumping the others; all must be defined in light of competing claims. As Lamer C.J. stated in Dagenais … "When the protected rights of two individuals come into conflict… Charter principles require a balance to be achieved that fully respects the importance of both sets of rights." This illustrates the importance of interpreting rights in a contextual manner - not because they are of intermittent importance but because they often inform, and are informed by, other similarly deserving rights or values at play in particular circumstances.24

Justice Iacobucci emphasizes this point in an article entitled "Reconciling Rights: The Supreme Court of Canada's Approach to Competing Charter Rights," when he states: "A particular Charter right must be defined in relation to other rights and with a view to the underlying context in which the apparent conflict arises."25

- Example: A person has a right to freedom of expression under the Charter, but they do not have a right to make child pornography.

In the context of freedom of belief or religion, the courts have found that the "freedom to hold beliefs is broader than the freedom to act upon them" where to do so would interfere with the rights of others.26

The Ontario Human Rights Code protects against discrimination on the basis of creed. But this protection does not extend to religious belief that incites hatred or violence against other individuals or groups, or to practices or observances that are said to have a religious basis, but which contravene the Criminal Code or international human rights principles.

Other examples include limiting the right to freedom of expression guaranteed by section 2(b) of the Charter where the expression could compromise a fair trial guaranteed by section 11(d) and section 7 of the Charter,27 incite hatred as defined in the Criminal Code of Canada and some human rights legislation,28 or result in discrimination against a minority group in our society.29

5.2 No hierarchy of rights

The Supreme Court of Canada has also been clear that there is no hierarchy of rights30 ム all rights are equally deserving and an approach that would place some rights over others must be avoided.31 No right is inherently superior to another right.32

- Example: In Dagenais v. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Supreme Court of Canada was asked to order a publication ban. The ban would have prevented the CBC from airing a mini-series showing a fictional account of sexual and physical abuse at a Catholic boy's school in Newfoundland during the trial of several members of a Catholic religious order. They were charged with physical and sexual abuse of young boys at schools in Ontario. The request for the publication ban required the court to balance the key constitutional rights of free expression (s. 2(b) of the Charter) and the right to a fair trial (s. 11(d)). Chief Justice Lamer stated:

- A hierarchical approach to rights, which places some rights over others, must be avoided, both when interpreting the Charter and when developing the common law. When the protected rights of two individuals come into conflict … Charter principles require a balance to be achieved that fully respects the importance of both sets of rights.33

5.3 Rights may not extend as far as claimed

When faced with a competing right scenario, organizations must assess whether the rights extend as far as the parties claim. This validation process has two main components:

- Does the claim engage a genuine legal right?

- When the evidence is examined, can the individual with the claim bring himself or herself within the asserted right?34

The courts have suggested that for a competing rights scenario to arise at all, a legal right must first be found to exist.35 When the facts and law are set out clearly, in context, not every rights claim will be found to be legally valid.

Human rights tribunals have considered and rejected several justifications for discriminatory conduct which could appear to be competing rights. For example, decision-makers have not accepted "customer preference" or "business or economic interests" as a valid competing right in cases involving discrimination contrary to human rights legislation.36

- Example: Organizations and individuals objecting to breastfeeding in public have claimed a "right" to request that a woman cover herself, move to a private area, etc. This right has sometimes been articulated as a freedom of expression claim. At first glance, there appears to be a conflict between freedom of expression and freedom from discrimination based on sex. But a careful consideration tells a different story. Court and Tribunal decisions have clearly established a woman's right to breastfeed in public.37 These decisions have concluded that actions which prevent a woman from breastfeeding in public are discriminatory. These precedents mean that in the absence of a compelling, equally valid right (or a Code defence such as health and safety), a woman has an unqualified right to breastfeed in public. Freedom of expression is not a valid counter-claim because there is no established positive legal right to individual preference. In other words, you may have an opinion about a woman breastfeeding in public, but you cannot use your preference to stop an activity that is already recognized as an established equality right.

If the claim does engage a legal right, it is then necessary to consider whether on the facts of the case, the individual can bring him or herself within that right. Evidence may need to be called to prove that the claim falls within the parameters of the right unless the engagement of the right is clear from the circumstances.38

In the case of Grant v. Willcock, a refusal to sell property to a racialized person did not fall under the right to liberty guaranteed by section 7 of the Charter. A human rights tribunal (formerly the "Board of Inquiry") found in the circumstances of the case that liberty rights did not extend to the liberty to discriminate based on a prohibited ground in the public sale of private property.39

5.4 Consider full context, facts and constitutional values

5.4.1 Context and facts

Once the competing issues are identified and described, the rights must be defined in relation to one another by looking at the context in which the apparent conflict arises.40 This approach is critical ム the courts have repeatedly held that Charter rights and human rights do not exist in a vacuum and must be examined in context to settle conflicts between them.

- Example: The Ontario Court of Appeal stated clearly in R. v. N.S.: "reconciling competing Charter values is necessarily fact-specific. Context is vital and context is variable."41

Supreme Court of Canada Justice Frank Iacobucci expressed a similar view:

- The key to rights reconciliation, in my view, lies in a fundamental appreciation for context. Charter rights are not defined in abstraction, but rather in the particular factual matrix in which they arise.42

..

Courts must be acutely sensitive to context, and approach the Charter analysis flexibly with a view to giving fullest possible expression to all the rights involved.43

Even slight variations in context may be critical in determining how to reconcile the rights. For example, in a situation that measures the right to freedom of expression against the impact of that expression on a vulnerable group, the precise tone, content and manner of delivery of the impugned message all have a significant impact on assessing its effect and the degree of constitutional protection it should be afforded. As noted by Justice Rosalie Abella in her dissenting judgement in Bou Malhab v. Diffusion M師rom仕ia CMR Inc., "[T]here is a big difference between yelling "fire" in a crowded theatre and yelling "theatre" in a crowded fire station."44

5.4.2 Underlying constitutional and societal values

As part of understanding the context, the constitutional and societal values at stake must be appreciated and understood.45 This "scoping of rights" allows some rights conflicts to be resolved.

Several considerations come into play in scoping the rights. A contextual analysis will often involve weighing the underlying values of Canadian society incorporated in various legal instruments and case law. For example, as the Supreme Court of Canada stated in R. v. Oakes, a case that set out the test for determining whether an infringement of Charter rights can be justified in a free and democratic society:

- The Court must be guided by the values and principles essential to a free and democratic society which I believe embody, to name but a few, respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, commitment to social justice and equality, accommodation of a wide variety of beliefs, respect for cultural and group identity, and faith in social and political institutions which enhance the participation of individuals and groups in society.

The underlying values and principles of a free and democratic society are the genesis of the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Charter and the ultimate standard against which a limit on a right or freedom must be shown, despite its effect, to be reasonable and demonstrably justified.46

The Preamble to the Ontario Human Rights Code, adapted from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, also reflects societal values with respect to human rights and equality. To this end, four key principles emerge from the Preamble:

- recognizing the dignity and worth of every person

- providing equal rights and opportunities without discrimination that is contrary to law

- creating a climate of understanding and mutual respect, so that

- each person feels a part of the community and able to contribute fully to the development and well-being of the community and the province.

Inherent in these values is a balancing47 of individual and group rights. The Preamble describes relational rights where the equality of each individual exists alongside community development and well-being. These values are not seen as hierarchical; one establishes and gives meaning to the other. In other words, the equality of each individual is fostered by creating a climate of mutual respect. At the same time, the community is fostered through the recognition of the inherent dignity and worth of each individual. The Preamble makes clear that human rights legislation does not simply deal with violations of equality rights ム it is also designed to foster an inclusive climate of mutual respect.48

International human rights law can also be an indicator of a society's underlying values. By endorsing an international convention, for example, Canada has publicly stated its commitment to uphold the values the convention contains.49

There have been cases where a person's objections to what they see as a violation of their rights have not been successful because their views are not consistent with society's underlying values on human rights and equality. Decision-makers should apply a contextual analysis that considers constitutional values and societal interests including equality rights of women, negative stereotyping of minorities, access to justice and public confidence in the justice system.50

- Example: Chamberlain v. Surrey School District No. 3651 involved a challenge to a school board's decision not to approve three books showing same-sex parented families as supplementary resources for use in teaching the family life curriculum. The Supreme Court of Canada noted that, while religious concerns of some parents could be considered, they could not be used to deny equal recognition and respect to other members of the community. The majority decision recognized the right to hold religious views, including the view that the practices of others are undesirable. But it emphasized that if a school is to function in an atmosphere of tolerance and respect, these views could not become the basis of school policy.

In Bruker v. Marcovitz52, the Supreme Court of Canada dealt with the relationship between freedom of religion and gender equality rights. A domestic dispute arose out of a husband's refusal to give his wife a religious divorce. The couple had signed an agreement to resolve their matrimonial disputes. The agreement included a term that the husband would give his wife a "get."53 However, for more than 15 years the husband refused to honour his commitment and argued that a civil court could not enforce the agreement he signed without violating his religious rights. The majority of the judges of the Supreme Court of Canada disagreed. They found that the contract was a valid and binding obligation and that the husband was not protected from liability for breaching the agreement based on freedom of religion. In doing so, they suggested that the wife's rights were a factor, and so too were fundamental values in Canadian society.54 The judges noted that the husband had "little to put on the scales" both because he had freely entered into an agreement which he later claimed violated his rights, and because to allow him to back out of it would offend public policy:

- The public interest in protecting equality rights, the dignity of Jewish women in their independent ability to divorce and remarry, as well as the public benefit in enforcing valid and binding contractual obligations, are among the interests and values that outweigh Mr. Marcovitz's claim that enforcing [the agreement] would interfere with his religious freedom.

Not all competing rights decisions deal with discrimination issues directly. But many of the values underlying human rights protections ム respect for human dignity, commitment to social justice and equality, accommodating a wide variety of beliefs and circumstances, protecting vulnerable persons and minority groups ム are important when deciding how to reconcile or appropriately limit rights.

5.5 Look at extent of interference

When rights appear to be in conflict, a key consideration is to determine if there is an actual intrusion of one right on the other, and the extent of the interference. If the interference is minor or trivial, the right is not likely to receive much, if any, protection.

- Example: In Syndicat Northcrest v. Amselem, a Jewish family was asked to remove a sukkah (a temporary hut placed on their balcony for religious celebration) because it did not comply with the condominium's by-laws and was interfering with the neighbours' enjoyment of their balcony. The Supreme Court refused to engage in a balancing process under section 1 of the Charter between freedom of religion as it affected the right to peaceful enjoyment and free disposition of property, since, in the Court's view, the effect on the Jewish family was substantial while the effect on the co-owners was "at best, minimal," and therefore limiting religious freedom could not be justified.55

Unless there is a substantial impact on other rights, there is no need to go further in the resolution process.

- Example: Providing rainbow stickers (which show support for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, transgender, intersex, queer, questioning, 2-spirited and allied communities) to a teacher, who could choose to display the stickers or not, was found not to create any burden or disadvantage on religious rights.56

Recognizing the rights of one group (e.g. the legalization of same-sex marriage) cannot, in itself, violate the rights of another (e.g. religious groups that do not recognize the right of persons of the same sex to marry) unless there is an actual impact on the rights of another (e.g. religious officials being asked to perform same-sex marriages). In Reference re Same-Sex Marriage, the Supreme Court of Canada stated:

- [T]he mere recognition of the equality rights of one group cannot, in itself, constitute a violation of the rights of another. The promotion of Charter rights and values enriches our society as a whole and the furtherance of those rights cannot undermine the very principles the Charter was meant to foster.57

Similarly, speculation that a rights violation may occur is not enough ム there must be evidence, and not just an unsupported assumption, that the enjoyment of one right will have a harmful effect on another.

- Example: Requiring teaching students in a religious teacher's college to follow certain "community standards" prohibiting "homosexual activity" does not mean that graduates of the teaching program will discriminate against or show intolerance towards their students based on sexual orientation.58

5.6 Core of right more protected than periphery

If there is a substantial interference with the rights in question, the rights must be weighed or balanced; one right will give way to the other or both rights will be compromised. It appears from the law that one set of rights is more likely to be restricted when an action would be contrary to the "core," or a fundamental aspect, of another individual's rights. For example, the courts have said that requiring religious officials to perform same-sex marriages contrary to their religious beliefs59 is different than allowing a person operating a business to refuse to offer his printing services to a same-sex organization on the basis that it violates his religious beliefs. In the latter case, the court noted that commercial enterprise is at the "periphery" of freedom of religion, and therefore, the religious rights had to give way to the right to be free from discrimination in services based on sexual orientation.60

The court stated:

- The further the activity is from the core elements of the freedom, the more likely the activity is to impact on others and the less deserving the activity is of protection. Service of the public in a commercial service must be considered at the periphery of activities protected by freedom of religion.61

The courts have consistently acknowledged that individuals are free to hold religious beliefs or express their opinions - but they have also made it clear that there are limits to how these beliefs and opinions may be acted upon where they may deny equal recognition and respect to other marginalized members of society. To this end, the private exercise of a right is generally given greater protection than the public exercise of a right.

- Example: The rights to freedom of expression and religion have been limited where the inherent dignity and equality of individuals protected under human rights legislation is significantly engaged, such as where the writings of a teacher were found to have poisoned the educational environment for his Jewish students.62

For one right to prevail over another, the impact on the core of the right must be shown to be real and significant in the circumstances. Yet, even where this is found to be the case, there is still a duty to accommodate the yielding right as much as possible.

5.7 Respect importance of both sets of rights

Where rights appear to be in conflict, Charter principles require an approach that respects the importance of both sets of rights, as much as possible.63 As noted in Supreme Court of Canada Justice Frank Iacobucci's article, and as cited with approval by the Ontario Court of Appeal:64

- …it is proper for courts to give the fullest possible expression to all relevant Charter rights, having regard to the broader factual context and to the other constitutional values at stake. 65

However, potential compromises to both sets of rights, recently described as "constructive compromises" by the Ontario Court of Appeal, are part of the reconciliation process. These compromises "may minimize apparent conflicts … and produce a process in which both values can be adequately protected and respected."66 Searching for compromises involves exploring measures that may lessen any potential harm to each set of rights.

This process of looking for options to reconcile competing human rights resembles the analysis under section 1 of the Charter and the process that must be followed as part of the duty to accommodate under human rights law. Similarly, in cases such as Dagenais v. Canadian Broadcasting Corp.,67 the Supreme Court directed courts considering a request for a publication ban to search for a "reasonably available and effective alternative measure" which would achieve the important objectives at stake.

When rights are in true conflict, some balancing may be required. One right may give way to another, or constructive compromises to both sets of rights may be found. In R. v. O'Connor,68 a case involving a victim's right to privacy in medical records and an accused person's right to make full answer and defence, a balance was achieved by first providing the disputed records to the court to review.

There may be rare cases where reconciling the rights in question is not possible. For example, in R. v. N.S.,69 the Ontario Court of Appeal acknowledged that while all rights are to be treated as equal at the outset, if there is no way to reconcile them, one right may be forced to give way to another. For example, when a conflict arises that truly harms an accused person's Charter right to make full answer and defence, that right will prevail. The countervailing right will have to yield as our justice system has always held that the threat of convicting an innocent person strikes at the heart of the principles of fundamental justice.70

5.8 Defences found in legislation may restrict rights

Human rights laws and the Charter contain exceptions that allow differential treatment in certain circumstances. In many cases, these defences were put into legislation to recognize competing rights and may reflect law-makers' efforts to reconcile a conflict between different rights.71

Often, statutory defences have been created to protect collective rights.72 They typically deal with matters such as religious education, the ability of certain types of organizations serving the interests of a particular group to restrict their membership to persons who belong to that group; the ability to restrict access to certain facilities and shared housing by sex; and the rights of religious officials to refuse to conduct marriage ceremonies contrary to their religious beliefs.

The Ontario Human Rights Code also includes provisions that appear to be attempts by the Legislature to reduce competing rights conflicts. The Preamble to the Code offers initial guidance for addressing conflicting rights by reflecting the values underlying the Code and human rights legislation in general. The Code also contains several exceptions that help to avoid situations where rights could potentially compete. The exceptions under the Code that most often emerge in competing rights cases are sections 13, 18, 18.1, 20(3), and 24. The eligibility criteria contained in each of these sections restricts to whom and in what circumstances these exceptions will apply.

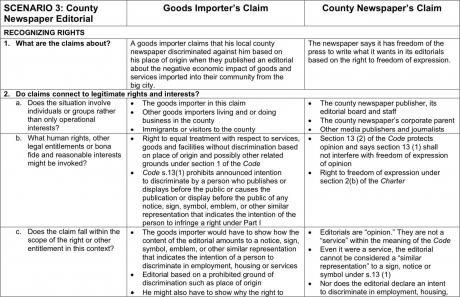

For example, section 13 of the Code attempts to balance a prohibition on an announced intention to discriminate with the freedom of expression of opinion.

- 13. (1) A right under Part I is infringed by a person who publishes or displays before the public or causes the publication or display before the public of any notice, sign, symbol, emblem, or other similar representation that indicates the intention of the person to infringe a right under Part I or that is intended by the person to incite the infringement of a right under Part I.

(2) Subsection (1) shall not interfere with freedom of expression of opinion.

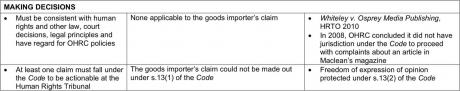

In recognition of the importance of freedom of expression as set out in this section, the OHRC intervened at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario in Whitely v. Osprey Media Publishing Inc. and Sun Media Corporation. The case involved an allegation that an editorial in The County Weekly News discriminated against people who have moved to Prince Edward County from elsewhere. The applicant alleged discrimination in services because of place of origin. The OHRC argued that section 13 of the Code does not restrict newspapers from printing opinions that some people may not like. In its decision, the Tribunal agreed, saying "…publication of opinion in the media is a matter at the core of freedom of expression and freedom of the press in a democratic society."73

In another example, section 18 of the Code addresses "special interest organizations":

- The rights under Part I to equal treatment with respect to services and facilities, with or without accommodation, are not infringed where membership or participation in a religious, philanthropic, educational, fraternal or social institution or organization that is primarily engaged in serving the interests of persons identified by a prohibited ground of discrimination is restricted to persons who are similarly identified.

This section applies only to services and facilities that are restricted based on membership or participation in an organization that primarily serves the interests of persons identified by a prohibited ground of discrimination (e.g. an Italian club for older persons). To qualify for an exception under this section, membership and participation must be restricted to persons who are similarly identified with the primary service interests of the organization. Therefore, this provision accommodates religious freedoms by allowing religious institutions to grant preferences in their admission policies or membership based on religion.74 The interpretation of this section in the case law balances freedom of association with equality rights. Like each of the other exception sections, this section considers the relationship between the private and public spheres. The public's right to be treated without discrimination must be considered against a private organization's right to limit its membership to an identified group.75

Section 1 is the primary site of internal balancing in the Charter. This section, also known as the "reasonable limits clause," allows the government to limit an individual's Charter rights. When the government has limited an individual's right, it has an onus to show, on a balance of probabilities, that the limitation was prescribed by law and is a reasonable limit in a free and democratic society. This is done by applying the "Oakes test." Simply put, the Oakes test considers:

- Whether there is a serious and important government objective

- Whether the way the government is trying to reach that objective is proportional (i.e. reasonable and justified). This consideration determines whether:

- (a)the government's measures are carefully designed to reach the objective

- (b)the approach used impacts on the rights at issue as little as possible

- (c)the benefits from the government's measures outweigh the seriousness of the impact on the rights.76

In a competing rights situation, the Oakes test should be applied flexibly to find a balance between the infringed right and the right the state seeks to foster to justify the infringement. Once again, this requires close attention to the full context in the particular circumstances of the case before the court.

- Example: The majority of the Supreme Court in B. (R.) v. Children's Aid Society77 found that the parents' decision to refuse a potentially life-saving blood transfusion for their baby was protected by freedom of religion. Using a process under the Child Welfare Act, the child had been made a temporary ward of the Children's Aid Society which had consented to the blood transfusion. However, despite the serious contravention of the parent's section 2(a) rights, the infringement was justified under section 1 of the Charter. The state interest in protecting children at risk was balanced against the parents' rights and found, in this case, to outweigh them.

Several things are clear when one reads the decisions that consider defences to discrimination in human rights statutes. First, unlike human rights defences that limit an individual's right based on other interests (such as financial undue hardship),78 defences that also recognize and promote the competing rights of other groups in society must not be interpreted overly narrowly. Second, despite this approach to interpretation, the defence has to be found to actually apply in the case at issue. Finally, this last point requires a full consideration of context based on the evidence in the circumstances of the case. In particular, the organization seeking to rely on the defence must be able to show, through objective evidence, the link between the actions that have a discriminatory impact on others and its enjoyment of its group right.

6. Analysis for addressing competing human rights situations

This section is based on a framework for addressing competing rights that the OHRC developed based on international human rights principles, case law, social science research, and consultation with community partners and stakeholders.79 The framework is set out in a summarized chart form at Appendix C.

The framework was developed with organizational settings in mind. This is where most competing rights situations happen and where they are best resolved. Employers, service providers, housing providers, unions and others have a legal obligation to address all human rights matters that may arise. This policy outlines a process to help organizations recognize and reconcile competing human rights claims. It is also an analysis tool that can be used by lawyers, mediators and adjudicators.

It is critical that all parties involved have a chance to be heard and to hear the perspectives of opposing parties. As the Ontario Court of Appeal has noted:

- If a person has a full opportunity to present his or her position and is given a reasoned explanation for the ultimate course of conduct to be followed, the recognition afforded that person's rights by that process itself tends to validate that person's claim, even if the ultimate decision does not give that person everything he or she wanted.80

By implementing the OHRC's proposed approach, organizations can be confident that they have a conflict resolution process in place that is consistent with human rights principles. The framework helps organizations recognize and address any power imbalances that may exist and take steps to empower all parties involved. Also, having an objective process removes some of the elements of individual discretion on the part of each decision-maker, and helps parties to feel they are being treated fairly and in accordance with standard procedures.

By following the approach outlined in the framework, organizations can take steps to resolve tension and conflict between parties at an early stage. Resolving conflicts early helps organizations to address matters before they fester and become entrenched. This in turn helps ensure the health and functioning of an organization, and can avoid costly and time-consuming litigation.

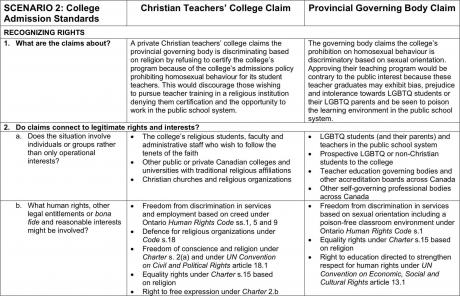

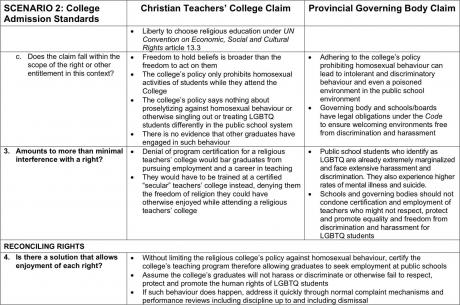

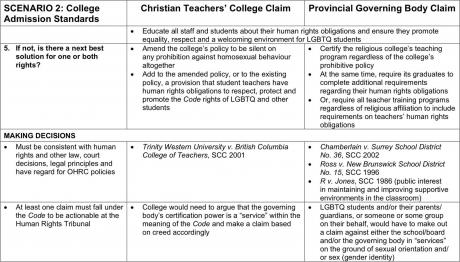

The following table summarizes the framework's three-stage, five-step process for recognizing and reconciling competing human rights claims:

Process for addressing competing human rights situations

Stage One: Recognizing competing rights claims

-

Step 1: What are the claims about?

-

Step 2: Do claims connect to legitimate rights?

-

(d) Do claims involve individuals or groups rather than operational interests?

-

(e) Do claims connect to human rights, other legal entitlements or bona fide reasonable interests?

-

(f) Do claims fall within the scope of the right when defined in context?

-

Step 3: Do claims amount to more than minimal interference with rights?

Stage Two: Reconciling competing rights claims

-

Step 4: Is there a solution that allows enjoyment of each right?

-

Step 5: If not, is there a "next best" solution?

Stage Three: Making decisions

-

Decisions must be consistent with human rights and other law, court decisions, human rights principles and have regard for OHRC policy

-

At least one claim must fall under the Ontario Human Rights Code to be actionable at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario

6.1 Stage One: Recognizing competing rights claims

At one point or another, most organizations will face situations where the values, interests and rights of individuals come into conflict. Stage One guides organizations to three areas of inquiry to help determine whether claims amount to competing human rights.

Recognizing whether the claims involve legal "rights" is a preliminary consideration separate from reconciling claims. This is a crucial part of the analysis, even if the organization does not believe the situation involves competing rights. It helps educate parties about their human rights and responsibilities, an especially important goal given the general lack of public awareness and ambiguity around rights and related language. This in turn may help parties frame their claims properly.

At the outset, parties should try to be open and suspend judgement. Often there is a tendency for rivals to deny the legitimacy of each other's rights claims. Working through this stage in a respectful and earnest way gives people a voice, helps diminish power imbalances (especially for historically marginalized groups), shows genuine consideration of different positions, and promotes the dignity of all claimants. It also encourages a spirit of cooperation that is very important for the reconciliation stage.

6.1.1 Step 1: What are the claims about?

Step 1 of the framework helps organizations draw out a detailed picture of each claim and the underlying situation or context. Parties should include facts, their perceptions about what happened, and views about the potential rights, values, and/or interests that may underlie the situation. It is important for parties to take part fully in this step. As one author notes:

- Hearing directly from the people affected is crucial to developing effective and responsive ways to resolve tensions between or among rights claims. Those who experience a denial of their rights have a unique perspective on why that is the case and appropriate remedies.81

A broad, inclusive approach will help to give a full appreciation of the social and factual context in which the conflict arises. Such an approach also helps to avoid dismissing relevant factors prematurely, and helps to frame claims properly. Only then can it be determined if the situation is actually one of competing rights.

6.1.2 Step 2: Do claims connect to legitimate rights?

Once the claims and context become clear under Step 1, organizations move to Step 2 to consider three questions to determine whether the claims connect to actual rights:

- (a) Do claims involve individuals or groups rather than operational interests?

- (b) Does at least one claim fall under a human right?

- (c) Do claims fall within the scope of the right?

(a) Do claims involve individuals or groups rather than operational interests?